Note: This blog post might be considered a continuation of this blog post, and part of a series that is more personal-journey.

Date and place: Oct. 31st, 2015, Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library, Indianapolis, Indiana.

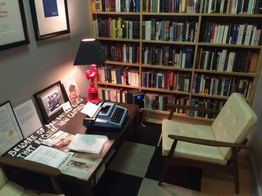

French writer and art-collector Noël Arnaud says “I am the space where I am,” and this is where I am now: sitting in a re-creation of Kurt Vonnegut’s home office, lounging in a very low, white, leather chair (low chairs, if you’d like to know about it, were the working-space preference for the six-foot fiction-writing man), beside a low table with a dark blue Smith-Corona electric typewriter on it, and a red-hen lamp (all Vonnegut’s once-upon-a-time), surrounded by shelves filled with books that, as the curator of this library/museum told me, have been deemed “what Kurt would’ve probably read.” I see a lot of classics, some contemporary novels, lots of odd sci-fi titles, and then, sensibly, a shelf of Danielle Steele romances beside Vonnegut’s own books in translation. The curator, a little embarrassedly, said he didn’t think Vonnegut would read those. “But they were donated,” he said and shrugged. I don’t know. Whether he would’ve read them or not I can’t say, but I think Kurt might’ve appreciated the break from all the stuffy seriousness of those classics.

There’s a quote in big block letters on the wall that reads: “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful what we pretend to be.”

It’s a point well taken Mr. Vonnegut.

Trip Update: Through Tennessee

For the last two weeks I’ve been wandering and wiling in the state of Tennessee. From the Smoky Mountains in the East to the Mississippi River in the West, up and down the Natchez Trace in the middle, with stops at such varied spiritual sites as The Farm, Graceland, and the Yellow Deli in Chattanooga (blogposts forthcoming). I drove through hills and farmland, watched the leaves turn, camped in the rain, dealt with a seemingly constant barrage of acorns falling on my tent in the nighttimes. I worried that these acorns were coming from the squirrels. That the day of their uprising had finally come. I worried for humanity.

At times, I found the same uneasiness that I started the trip with creeping back into my mind. Who am I and what am I doing here? became the questions that visited me in the hours of darkness, alone in my tent, the campfire out, not quite tired enough to sleep (because it was 8pm), my mind trying to parse and understand the experiences of the weeks so far in these varied spiritual communities. I blame Mr. Levine, my high school English teacher, for these questions. It’s not the first time they’ve haunted me. Ever since he assigned them for a paper senior year, they periodically do just that. (Admittedly, they also periodically propel me into those ever-deepening quests for meaning and understanding, so, you know, I’m also forever grateful or whatever to you, Mr. Levine, if you’re reading.)

Is the Universe On My Side Revisited

I’m not going to answer those questions from senior year of high school, just like I didn’t answer them then (and still managed a B+ on the paper! Hoo-ah!). I still don’t know how. But their return prompts me to revisit the question I asked a month ago, back at the beginning of this trip, about my own belief. Back then I asked: is the Universe “on my side?” Or, maybe a little more complicatedly (because that’s how I roll): Is it prudent to approach this trek with the belief that the Universe is on my side? That the energies of spirit or God or maple syrup, whatever it is, the one that pervades the entirety of existence, are somehow conspiring on my behalf?

I chose skepticism. The Universe is the Universe, I wrote, it doesn’t take sides. Really, I felt a kind of immediate moral objectionability to the premise. If pronoia, as Philip K. Dick calls it, is real - if there is a conspiracy masterminded by the Vast Active Living Intelligence System on my behalf - then what to say to those many many people, my neighbors, my friends, my ancestors (who I pay homage to on this Samhain holiday), who currently have, have had and will have, injustices perpetrated against them? That the Universe is also on their side but…maybe they don’t get it? Or that it just prefers me over them? I thought: if I believe that the Universe is on my side, then I am obligated to believe that it’s on everybody’s side, because in my conception of God, there are no preferred individuals, no elect. And, looking at the world with all its moral perversions, I just couldn’t let myself believe such a thing.

Abstractly speaking, this seemed like the morally proper approach.

And yet...

Morality: Abstract vs. Concrete, Utilitarianism vs. The Categorical Imperative

I’m beginning to smell a stink in the ointment. My abstract reasoning, I fear, has actually made it more difficult to actually act morally.

Many a book and philosophy PHD dissertations have been (will be, are being, etc.) written about the tensions of Millian Utilitarian ethics and the Kantian Categorical Imperative; the abstract approach vs. the concrete, personal approach to making ethical, moral decisions. I’d like to avoid writing a dissertation here. I’m embedding a link to a TED talk in which a professor of philosophy, speaking to a group of a few hundred Silicon Valley computer-science programers, brings these questions up and pressures his crowd to think about them. At central issue: is living morally better approached through the abstraction of doing what is best for the greatest number, or in the more concrete sense of treating every individual (including oneself) as having inherent worth?

In answering my question about the Universe, I think I took the Utilitarian approach. I came at the question from the angle of rational abstraction, not personal experience. And that’s where I’m sniffing the stink.

Why? I can't claim to have any final answer on this, but here's my thinking at the moment: If the suffering of others means that I am morally obligated to believe in the indifference of the Universe, then I’m living right back in the absurdity of existence, on that short road to nihilism, and that's right where I don’t want to be. If I’m not allowing myself to believe in a Universe that cares (albeit maybe in a way I don’t comprehend), a Universe that knows and understands, then whatever blessings I have (good health, loving family, good friends) are really not blessings at all, they're burdens. If I, and not the Universe, am implicated in the suffering of humankind, then I’m not just responsible for my fellow human beings, I’m also guilty of the injustices committed against them, just by dint of what I have and others do not. Moral decisions then are not made for their own sake, but to unburden this guilt. Maybe this works for some, but for me, I run out of gas quickly. Thing is: saddling myself with guilt, placing that heaviness upon my shoulders leads to such exhaustion that I have little little strength left to go out and try to do good in a world that needs it.

So if the moral obligation doesn’t then come in believing in a Universe that is equally blind to all (so this internal out-loud wrangling goes), what’s the flip side? Here’s my thought as I work to make the difficult move into living more in harmony with a belief in the Oneness: an individual’s morality is born of his/her/gender-neutral-pronoun’s own depths. It begins in the difficult and continual work of unmasking and reaching for one’s deepest desires (maybe of being periodically haunted by the questions: who am I and what am I doing here?), and then it continues in using the knowledge and wisdom gained therein to be a better person, neighbor, friend, sibling, child. In lifting up the people around us. Rather than gleaning morality from an abstraction interpreted inward - what we might call "the ole outside-in tactic" - it works the other way: from the inside out.

And as to the Universe? I won’t claim to speak for it, but yes, I think the Universe will help with all that. Why? Because that’s the only way things get better. Because our deepest desires, complex and individualized as they may feel and indeed be, might, at the same time be identical for all of us (there it is again: A is A and Not A). Just what are these same deep desires? The overcoming of fear. The sharing of love.

Conclusion

So I’m changing my answer. “You are what you pretend to be,” says ole Kurt from the wall, “so be careful.” I think maybe I was not quite careful enough in choosing to pretend at skepticism. After all, the opiate of the Oneness, of trust in it, of pursuing love as a means of worship through all the brick-a-brack complexities of life, that opiate really only works if you want it to. And I want it to.

The teaching of the Jew of Pshishke was that in one pocket we have a piece of paper on which it is written, “I am but dust and ashes,” and in the other pocket, “The whole world was created for me,” and that we must learn how to choose when to reach into each pocket. So? I suppose I’m reaching into the other pocket.

The Kotzker Rebbe said, “God lives where is He allowed to live.” Anachronistic gendered language of God as “He” notwithstanding, here I am a month into this travel, and I’m letting God in. I’m paying attention. I’m believing the signs, in the non-randomness of coincidence. I’m trusting. When I speak to the Universe, and when I listen, it speaks back.

Now it’s saying: You can’t stay here, the library is closing.

Date and place: Oct. 31st, 2015, Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library, Indianapolis, Indiana.

French writer and art-collector Noël Arnaud says “I am the space where I am,” and this is where I am now: sitting in a re-creation of Kurt Vonnegut’s home office, lounging in a very low, white, leather chair (low chairs, if you’d like to know about it, were the working-space preference for the six-foot fiction-writing man), beside a low table with a dark blue Smith-Corona electric typewriter on it, and a red-hen lamp (all Vonnegut’s once-upon-a-time), surrounded by shelves filled with books that, as the curator of this library/museum told me, have been deemed “what Kurt would’ve probably read.” I see a lot of classics, some contemporary novels, lots of odd sci-fi titles, and then, sensibly, a shelf of Danielle Steele romances beside Vonnegut’s own books in translation. The curator, a little embarrassedly, said he didn’t think Vonnegut would read those. “But they were donated,” he said and shrugged. I don’t know. Whether he would’ve read them or not I can’t say, but I think Kurt might’ve appreciated the break from all the stuffy seriousness of those classics.

There’s a quote in big block letters on the wall that reads: “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful what we pretend to be.”

It’s a point well taken Mr. Vonnegut.

Trip Update: Through Tennessee

For the last two weeks I’ve been wandering and wiling in the state of Tennessee. From the Smoky Mountains in the East to the Mississippi River in the West, up and down the Natchez Trace in the middle, with stops at such varied spiritual sites as The Farm, Graceland, and the Yellow Deli in Chattanooga (blogposts forthcoming). I drove through hills and farmland, watched the leaves turn, camped in the rain, dealt with a seemingly constant barrage of acorns falling on my tent in the nighttimes. I worried that these acorns were coming from the squirrels. That the day of their uprising had finally come. I worried for humanity.

At times, I found the same uneasiness that I started the trip with creeping back into my mind. Who am I and what am I doing here? became the questions that visited me in the hours of darkness, alone in my tent, the campfire out, not quite tired enough to sleep (because it was 8pm), my mind trying to parse and understand the experiences of the weeks so far in these varied spiritual communities. I blame Mr. Levine, my high school English teacher, for these questions. It’s not the first time they’ve haunted me. Ever since he assigned them for a paper senior year, they periodically do just that. (Admittedly, they also periodically propel me into those ever-deepening quests for meaning and understanding, so, you know, I’m also forever grateful or whatever to you, Mr. Levine, if you’re reading.)

Is the Universe On My Side Revisited

I’m not going to answer those questions from senior year of high school, just like I didn’t answer them then (and still managed a B+ on the paper! Hoo-ah!). I still don’t know how. But their return prompts me to revisit the question I asked a month ago, back at the beginning of this trip, about my own belief. Back then I asked: is the Universe “on my side?” Or, maybe a little more complicatedly (because that’s how I roll): Is it prudent to approach this trek with the belief that the Universe is on my side? That the energies of spirit or God or maple syrup, whatever it is, the one that pervades the entirety of existence, are somehow conspiring on my behalf?

I chose skepticism. The Universe is the Universe, I wrote, it doesn’t take sides. Really, I felt a kind of immediate moral objectionability to the premise. If pronoia, as Philip K. Dick calls it, is real - if there is a conspiracy masterminded by the Vast Active Living Intelligence System on my behalf - then what to say to those many many people, my neighbors, my friends, my ancestors (who I pay homage to on this Samhain holiday), who currently have, have had and will have, injustices perpetrated against them? That the Universe is also on their side but…maybe they don’t get it? Or that it just prefers me over them? I thought: if I believe that the Universe is on my side, then I am obligated to believe that it’s on everybody’s side, because in my conception of God, there are no preferred individuals, no elect. And, looking at the world with all its moral perversions, I just couldn’t let myself believe such a thing.

Abstractly speaking, this seemed like the morally proper approach.

And yet...

Morality: Abstract vs. Concrete, Utilitarianism vs. The Categorical Imperative

I’m beginning to smell a stink in the ointment. My abstract reasoning, I fear, has actually made it more difficult to actually act morally.

Many a book and philosophy PHD dissertations have been (will be, are being, etc.) written about the tensions of Millian Utilitarian ethics and the Kantian Categorical Imperative; the abstract approach vs. the concrete, personal approach to making ethical, moral decisions. I’d like to avoid writing a dissertation here. I’m embedding a link to a TED talk in which a professor of philosophy, speaking to a group of a few hundred Silicon Valley computer-science programers, brings these questions up and pressures his crowd to think about them. At central issue: is living morally better approached through the abstraction of doing what is best for the greatest number, or in the more concrete sense of treating every individual (including oneself) as having inherent worth?

In answering my question about the Universe, I think I took the Utilitarian approach. I came at the question from the angle of rational abstraction, not personal experience. And that’s where I’m sniffing the stink.

Why? I can't claim to have any final answer on this, but here's my thinking at the moment: If the suffering of others means that I am morally obligated to believe in the indifference of the Universe, then I’m living right back in the absurdity of existence, on that short road to nihilism, and that's right where I don’t want to be. If I’m not allowing myself to believe in a Universe that cares (albeit maybe in a way I don’t comprehend), a Universe that knows and understands, then whatever blessings I have (good health, loving family, good friends) are really not blessings at all, they're burdens. If I, and not the Universe, am implicated in the suffering of humankind, then I’m not just responsible for my fellow human beings, I’m also guilty of the injustices committed against them, just by dint of what I have and others do not. Moral decisions then are not made for their own sake, but to unburden this guilt. Maybe this works for some, but for me, I run out of gas quickly. Thing is: saddling myself with guilt, placing that heaviness upon my shoulders leads to such exhaustion that I have little little strength left to go out and try to do good in a world that needs it.

So if the moral obligation doesn’t then come in believing in a Universe that is equally blind to all (so this internal out-loud wrangling goes), what’s the flip side? Here’s my thought as I work to make the difficult move into living more in harmony with a belief in the Oneness: an individual’s morality is born of his/her/gender-neutral-pronoun’s own depths. It begins in the difficult and continual work of unmasking and reaching for one’s deepest desires (maybe of being periodically haunted by the questions: who am I and what am I doing here?), and then it continues in using the knowledge and wisdom gained therein to be a better person, neighbor, friend, sibling, child. In lifting up the people around us. Rather than gleaning morality from an abstraction interpreted inward - what we might call "the ole outside-in tactic" - it works the other way: from the inside out.

And as to the Universe? I won’t claim to speak for it, but yes, I think the Universe will help with all that. Why? Because that’s the only way things get better. Because our deepest desires, complex and individualized as they may feel and indeed be, might, at the same time be identical for all of us (there it is again: A is A and Not A). Just what are these same deep desires? The overcoming of fear. The sharing of love.

Conclusion

So I’m changing my answer. “You are what you pretend to be,” says ole Kurt from the wall, “so be careful.” I think maybe I was not quite careful enough in choosing to pretend at skepticism. After all, the opiate of the Oneness, of trust in it, of pursuing love as a means of worship through all the brick-a-brack complexities of life, that opiate really only works if you want it to. And I want it to.

The teaching of the Jew of Pshishke was that in one pocket we have a piece of paper on which it is written, “I am but dust and ashes,” and in the other pocket, “The whole world was created for me,” and that we must learn how to choose when to reach into each pocket. So? I suppose I’m reaching into the other pocket.

The Kotzker Rebbe said, “God lives where is He allowed to live.” Anachronistic gendered language of God as “He” notwithstanding, here I am a month into this travel, and I’m letting God in. I’m paying attention. I’m believing the signs, in the non-randomness of coincidence. I’m trusting. When I speak to the Universe, and when I listen, it speaks back.

Now it’s saying: You can’t stay here, the library is closing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed