I heard about them on a tip back at the beginning of this adventure into the cavernous trenches of American spirituality. Early in October, I contacted Rami Shapiro, a rabbi based out of Murfreesboro Tennessee. We talked some about the variety of religions, and a little about the Perennial Philosophy (that all mystical traditions share the heart of belief in the Oneness). He asked me if, on this trip around the states, I was going to be searching for “the real God?” I said, well, yes (is there any other answer to such a question, under the circumstances?). “If you’re looking for the real God,” he said, “make sure to meet Sheikh Kabir and Sheikha Camille Helminski. They’re Sufis in Louisville.”

So, after my time with the Root and Branch Church, I went there.

Sufism and The Fringe

As has been mentioned on this blog, fringe can mean many things. To date, in these travels I've found: The physical fringe, where groups of people find their own land away from the rest of society and live out the experiments of permaculture living and spirituality-based Community building (places like Earthaven and The Farm). There is the new fringe, where innovative attempts at revitalizing one of the mainstream religious traditions can take place (Christianity at Root and Branch). And then there is the ancient fringe, where practitioners of (usually mystical) traditions have stayed, by push or by draw, on the outskirts of a mainstream religion. The Sufi mystics of Islam fit squarely into this third category.

Threshold Society of Louisville: Breathing and Chanting and Breathing and Meditating and Chanting and Breathing and Whirling and Chanting….

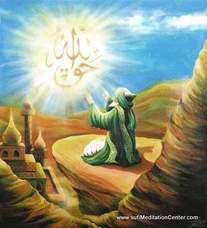

On a long street of houses in the Highlands of Louisville, the Threshold Society meets two Thursdays a month for a few hours of meditation, discussion, zhikr - which includes the traditional Sufi practices of chanting the name and praises of God (Allah) - and, of course, the whirling of the dervishes.

I arrived just before 8pm to a living room filling quietly with people. It was a diverse lot: young and old, coming from what appeared to be the veritable American spectrum of ethnic backgrounds, two women in hijabs, and many without, couples and singles. I shook hands with Sheikh Kabir, in whose home the Society meets, and found a seat. The chairs and couches were arranged around a space with a cleared coffee table at the center (this would later be moved for the lone dervish who whirled on behalf of everyone), and with two plush seats at the head where sat Kabir and Camille, our leaders for the evening.

Most of the attendants sat silently, a few whispered to each other, as we waited for Kabir and Camille to take their seats. But for the incense burned and the soft prayer music playing, we might have been gathered for a book club. Once the Sheikh and Sheikha sat, the service began. “We open in the name of the source of life,” Kabir spoke with his hands raised in a gesture of prayer, “bismillah.” At this, everyone closed their eyes and began to meditate. There was little talking. The atmosphere of potential book club was gone as everyone sat with their eyes closed, and Kabir offered a few instructions for focused breathing. “Breathe into presence,” he said, “grateful and aware.” This lasted for some time until Kabir directed that we begin to intone the sound “hu” on our out breaths. Soon all of us were in sync, focused and aware (as instructed) of the singular humming frequency that our collective breaths were creating.

I’ve written previously about the inherent tension between the individual and the group in religious services, that basic difficulty of feeling fully oneself, and a member of a singular collective, all at once. At the root of the Sufi practice I found the dissolution of this tension. While some of the religious services I’ve been to on these travels have used meditation, and some chanting, and some singing, and others dancing, the Threshold Society did all of those things. Each part of the service therefore became an attempt at pushing deeper into the realm where such distinctions are resolved, where all individual inner truths are connected in, as Kabir said, that singular “source of life.” (Really, it’s pretty amazing how focusing for a long time on breathing and chanting and singing will do just that. I’ll go ahead and say it: I was pretty amazed.) This is one way of achieving an experience - fleeting though it may be - of connection with the Oneness.

And really, this was the majority of the service: following the meditation and shared hums of our breathing, we chanted simple Arabic prayers, did more breathing, more chanting, some singing, and had a discussion before the final round of chanting (just the word “Allah”), which included drums and the aforementioned dervish. (Here’s a video of some whirling dervishes in Turkey).

The Discussion

Our discussion was facilitated by a handout. On it was a short paragraph on “deconditioning” and then a traditional story about overcoming vanity, as written by Kabir. The notion of “deconditioning” is central to the Sufi philosophy. To sum it up, as written on the handout, “[…] a deeper understanding of the spiritual process is when we realize that we are more in need of losing things than adding more to ourselves.” In this way, Kabir explained, the individual moves toward the highest level of living experience: haqiqah, or “inner truth.” This is a sharp contrast to what’s considered progress in much of the traditional spiritual world. In many (maybe most) formulations, self improvement and achievement of virtue and merit are sought, in theory, to weigh the balances of good on our behalf. To the Sufi, this way of thinking is a trap. Seeking more is a means of becoming blind and deaf to the quiet inner truth. Moral goodness, so the philosophy goes, flows naturally when one is in touch with this inner truth. By the same token, this is also different linguistically from many meditative and spiritual practices that preach annihilation of the self, as inner truth can only be experienced by going deep into the self.

So what does that mean? Aha, the story. In it, one respected Sufi Sheikh (Abu Shams) visits a second Sheikh who promptly brags to the first that “in our order we strictly follow the sacred law, read the classic stories, and make use of the special esoteric technology controlling the breath, and all this with the blessing and guidance of the Qutub, the Pole of the Age.” Abu Shams proceeds, over the course of the story, to show the second Sheikh the fundamental transience of each of those virtues he’s touted so hubristically for his order. All of the virtues that the second Sheikh has accumulated, Abu Shams strips him of. Slowly, by the machinations of Abu Shams, all of the students of the second Sheikh leave him.

The second Sheikh is overcome with disillusionment and comes to Abu Shams. He asks to become his student. And for Abu Shams’ response, I’ll quote Kabir’s story in full, as it seems to get pretty succinctly to the root of Sufi thought:

“ ‘Until you see that you desire and need other people to rely on you for own sense of self-worth, as long as you crave the satisfaction of being an authority, you cannot be entrusted with the truth of the teaching, nor transmit it to other. The teaching is like Air; everyone is sustained by it whether they know it or not, but it cannot be bought or sold through the bargaining and strategies of the ego, not through selfish pleasures, nor through mysterious signs of guidance that only confirm your self-importance, nor even through the most extreme efforts and sacrifices.’

(The second Sheikh responds:) ’But the tradition has always advised that spiritual practices, sacrifice and effort are essential to spiritual progress.’

‘Yes,’ said Abu Shams, ‘but such advice was meant for people who had first overcome their vanity.’ ”

Haqiqah, Inner Truth. Taqwa, Conscious and Cautionary reverence. These are the key terms of the pursuit of God in Sufism. So what are they really? Just what is “deconditioning”? Perhaps not much more than the enjoinder to cultivate and remember the simplest of humility.

Some More From The Evening: Community, and an Abstract vs. Concrete God

“We are not mystics who leave society behind,” Kabir tells me later in the evening, after the service has concluded, “we aim for practical mysticism.” And this is a sentiment I deeply appreciate, though I think (and I’m guessing the Helminskis might agree) such aims can be pretty difficult to attain. As to what it means to be a practical mystic, many in the group tell me of the successes that they've found as a Community, finding deeper connections to each other through the meetings and the guidance of the Helminskis. Much like Root and Branch, the cultivation of Community, of helping each other through difficulties and sharing each other's joys, is one of the central aims of the Threshold Society of Louisville.

In that same discussion about practical mysticism, I ask Kabir about my difficulties with evil in the world, and the notion of an abstract God. Kabir tells me, “I have never been able to believe in any kind of abstract God, only the concrete God that I see in the love and deeds of other people.”

It’s a beautiful idea, one I find myself experiencing more with every day that passes on this trip. It makes sense, especially following the intensity of the Sufi service. Consider: When worship is done by stripping oneself down, by methodically taking apart and silencing all of those abstract and ethereal competing voices and selves that make up one’s interiority on any given day, until all that’s left is the individual heart, beating by its own electricity, an electricity derived from…somewhere, how could it be otherwise? What’s more concrete than a beating heart?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed